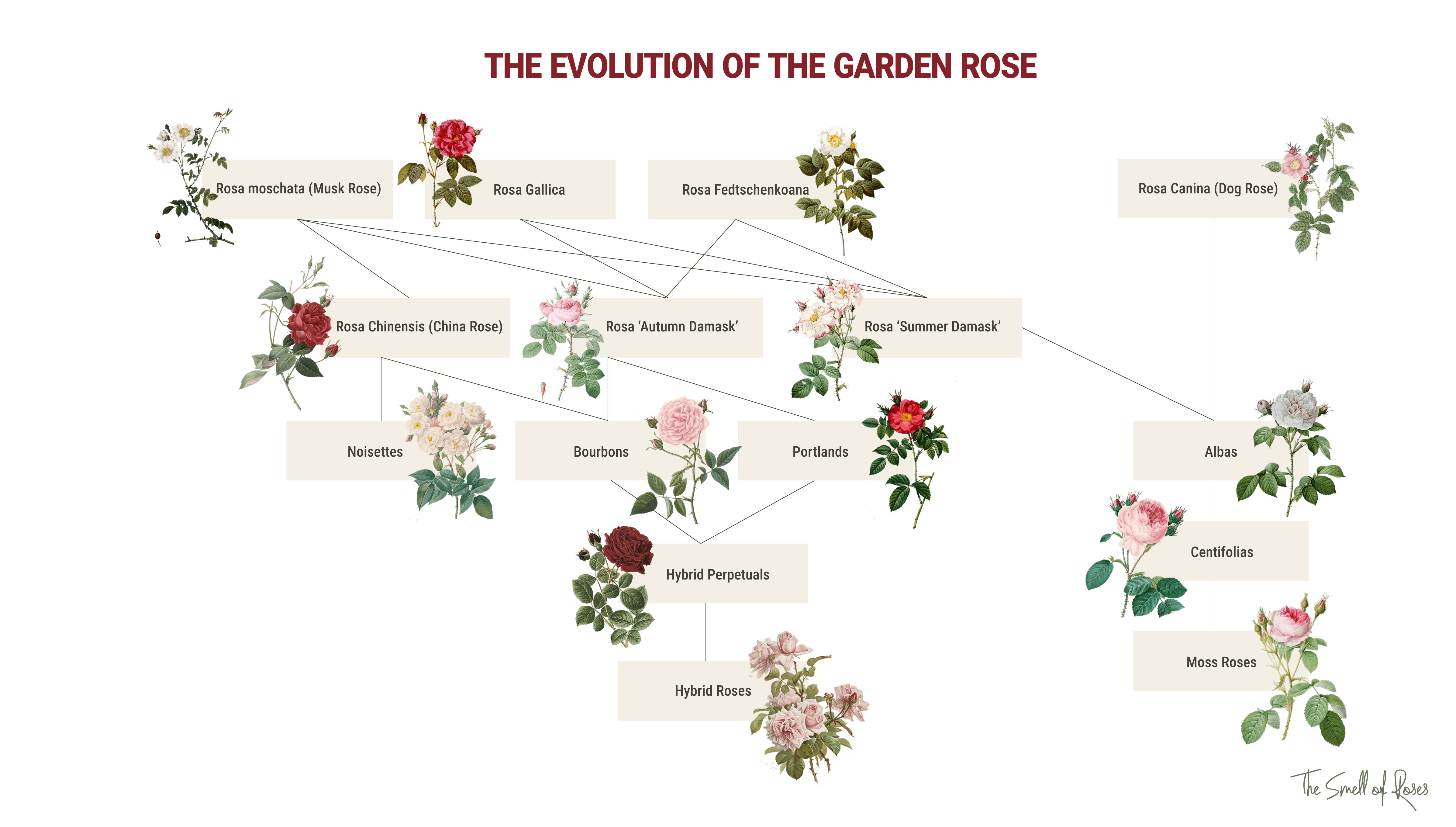

Like a carefully orchestrated symphony that unfolds over millennia, the evolution of the garden rose represents one of humanity's most remarkable collaborations with nature. From ancient Asian slopes to European monastery gardens, from Charleston rice plantations to modern laboratories, the rose has transformed from simple wild flowers into the complex beauties that grace today's gardens. The story begins 30 million years ago with ancestors bearing single yellow petals, yet reaches its crescendo in the bustling markets and botanical gardens of our contemporary world.

Recent genetic analysis reveals that the first roses likely bore yellow flowers with single petals, a far cry from the multi-petalled crimson and pink varieties that captured human imagination. These ancient predecessors evolved across Asia, Europe, and North America, eventually giving rise to the foundational species that would become the building blocks of all modern roses.

What follows is the whistle-stop tour of the garden rose evolution.

The Ancient Foundations: Wild Species and Early Cultivars

Rosa Gallica: The European Pioneer

Among the oldest cultivated roses stands Rosa Gallica, often called the French Rose or the Apothecary's Rose. Native to central and southern Europe, including France - hence its name meaning "rose of Gaul" - this species became the backbone of European rose culture. Archaeological evidence suggests Rosa Gallica was cultivated as early as the 12th century BC, making it potentially the oldest identified rose in cultivation.

The species proved remarkably adaptable, spreading rapidly through underground runners and displaying compact growth with rough, distinctive leaves. Its most famous cultivar, Rosa Gallica 'Officinalis', earned the moniker "Apothecary's Rose" for its extensive use in medieval medicine. This semi-double rose became so significant that it was adopted as the royal badge of the House of Lancaster in 13th century of the Roses.

The Mysterious Musk Rose

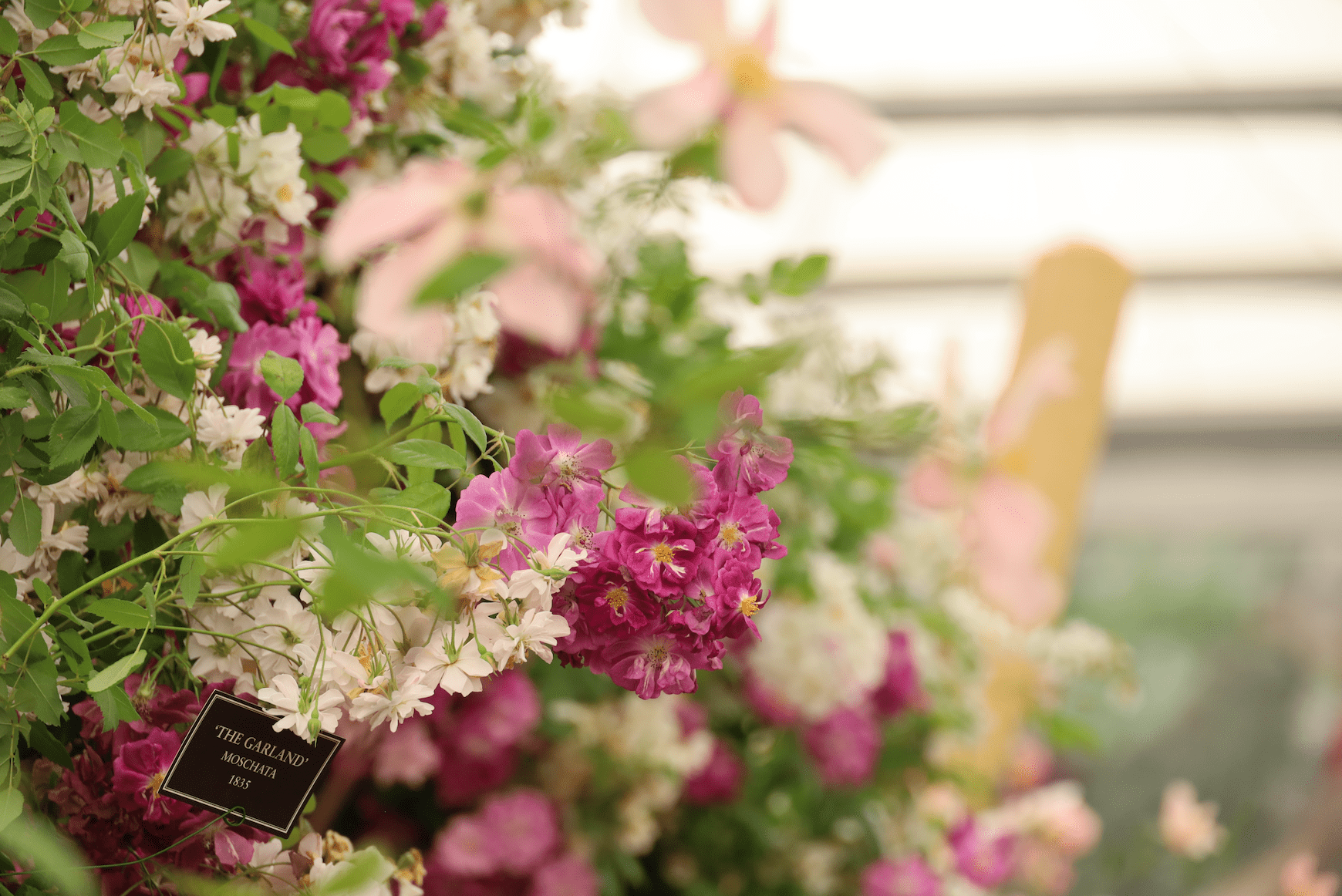

Rosa Moschata, the musk rose, presents a more enigmatic tale. Its wild origins trace to southern Iran and Afghanistan, though it has been cultivated for so long that truly wild specimens may no longer exist. This climbing species, reaching up to 3 metres in height, produces distinctive white flowers in loose clusters, blooming from late spring through autumn in warm climates.

The musk rose's contribution to garden rose evolution cannot be overstated. Shakespeare immortalised it in "A Midsummer Night's Dream", and it became a parent to several crucial rose groups, notably the damask roses and later the noisette roses. Its characteristic musky scent, emanating from the stamens, passed to many of its descendants, becoming a signature of refined fragrance in garden roses.

Rosa Fedtschenkoana: The Hidden Genetic Key

Perhaps no wild rose has been more underappreciated than Rosa Fedtschenkoana, discovered by Russian botanist Olga Fédchenko in Central Asia. This hardy species, native to the foothills of the Tian Shan and Pamir-Alai mountain ranges, remained largely unknown until recent DNA analysis revealed its crucial role in rose evolution.

Rosa Fedtschenkoana possesses the rare ability to bloom repeatedly throughout the growing season, a trait that would prove invaluable to rose breeders. Modern genetic research has shown that this species, along with Rosa Moschata and Rosa Gallica, contributed to the development of damask roses, particularly the autumn-blooming varieties. Its pale greyish-green foliage and small white flowers belie its fundamental importance in providing the "remontant gene" that enables repeat flowering in European roses.

The Dog Rose: Europe's Wild Foundation

Rosa Canina, commonly known as the Dog Rose, represents Europe's most widespread wild rose species.

This variable climbing shrub, native to Europe, northwest Africa, and western Asia, typically reaches 1-5 metres in height with characteristic hooked prickles that aid its climbing habit.

The dog rose's botanical peculiarity lies in its unusual genetic makeup. Most commonly pentaploid (having five sets of chromosomes instead of the typical two), it employs a unique form of reproduction called "permanent odd polyploidy". During reproduction, only seven chromosomes pair normally, while the remainder are included in egg cells but not pollen - a genetic innovation that has enabled this species to thrive across diverse European landscapes.

Historically, the dog rose derived its name from ancient beliefs that its roots could treat rabies and dog bites. More importantly for rose evolution, it served as a parent species for the alba roses and contributed genetic material to numerous other garden rose classes.

The Eastern Revelation: China Roses Transform the West

Rosa Chinensis: The Game Changer

The introduction of Chinese roses to Europe in the late 18th century marked perhaps the most significant turning point in rose breeding history. Rosa Chinensis, native to Southwest China in Guizhou, Hubei, and Sichuan provinces, had been cultivated in Chinese imperial gardens for over 2,000 years.

Unlike their European counterparts, Chinese roses possessed the extraordinary ability to bloom repeatedly throughout the growing season - up to 200 days per year compared to the single annual flowering of European varieties. This trait, known as "remontancy," would revolutionise rose breeding when Chinese varieties reached European shores.

The arrival of Chinese roses in Europe occurred gradually through the East India Company's trade networks. Empress Josephine, Napoleon's first wife and passionate rose collector, played a crucial role in popularising these eastern varieties at her garden in Malmaison. The genetic contribution of Chinese roses proved so fundamental that most modern garden roses trace their repeat-flowering ability to these Asian ancestors.

The Great Hybridisation: East Meets West

Damask Roses: The Ancient Aromatics

The damask roses (Rosa × damascena) represent one of history's most successful natural hybridisations. Named after Damascus, Syria, these roses emerged from crosses between Rosa Gallica, Rosa Moschata, and, as recent DNA analysis has revealed, Rosa Fedtschenkoana.

Damask roses exist in two primary forms: Summer Damasks, which bloom once per season, and Autumn Damasks, which provide repeat flowering. The autumn-blooming varieties proved particularly significant, as they were among the first European roses to demonstrate remontant characteristics, likely inherited from their Rosa Fedtschenkoana parentage.

These roses became legendary for their intense fragrance, making them the foundation of the perfume industry in regions like Grasse, France, and the Rose Valley of Bulgaria. Their commercial cultivation for rose oil and rose water continues today, particularly in Morocco, Iran, and Turkey.

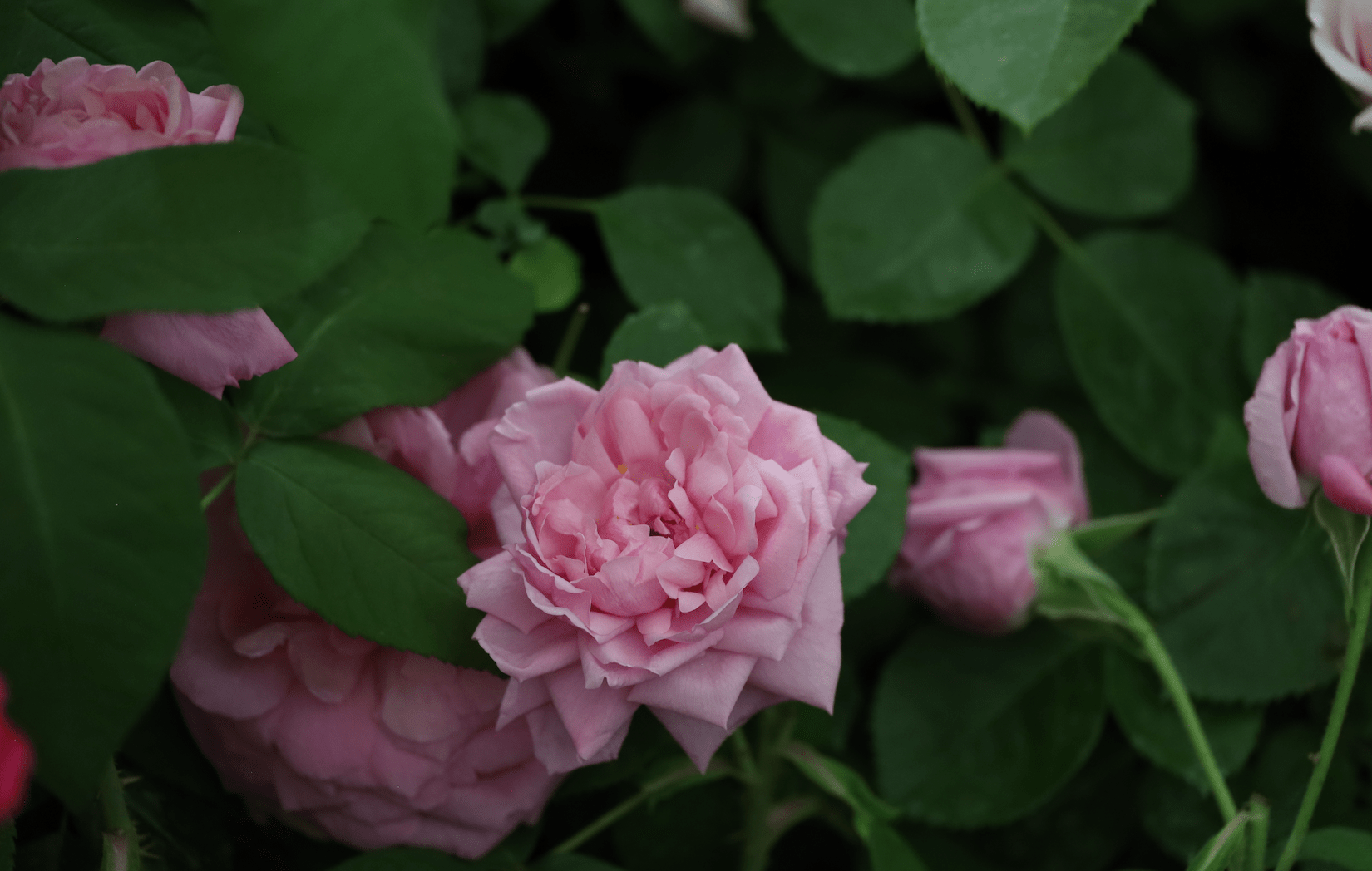

Alba Roses: The White Rose of York

The alba roses (Rosa × Alba) emerged as hybrids between Rosa Gallica and Rosa Canina, creating some of the most refined and hardy garden rose. The oldest alba rose, known as 'Semiplena', became the white rose that the Yorkists chose as their badge during the 15th century Wars of the Roses.

These roses exhibit exceptional hardiness and disease resistance, thriving in conditions that challenge other rose classes. Their distinctive bluish-green foliage and refined fragrance - often compared to white hyacinths or spicy apples - make them immediately recognisable. The alba roses proved so robust that they became popular choices for creating winter-hardy varieties suitable for northern Scandinavia and Canada.

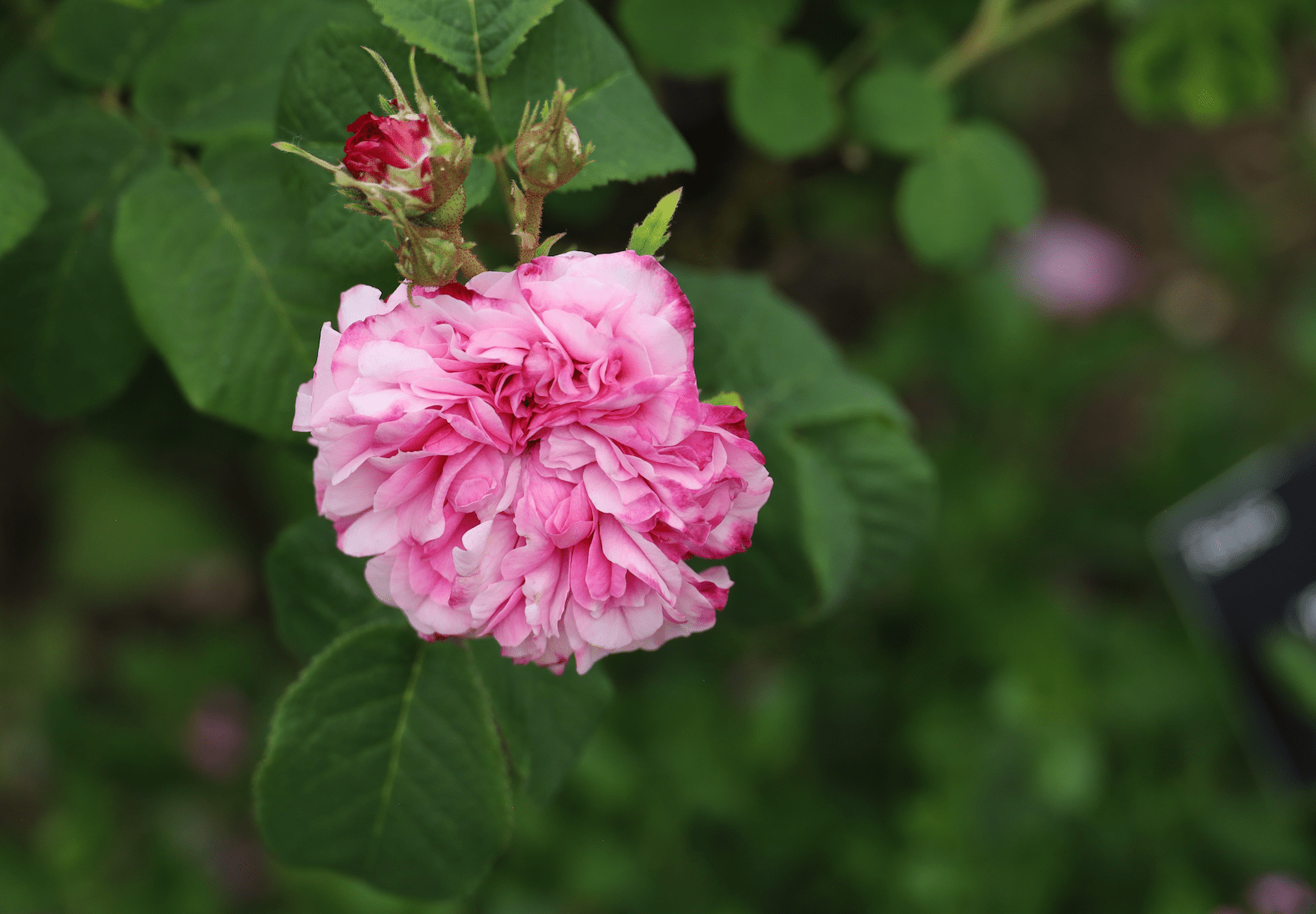

Centifolia Roses: The Hundred-Petalled Wonders

The Centifolia roses, also known as cabbage roses or Provence roses, represent the pinnacle of Dutch rose breeding between the 17th and 19th centuries. These complex hybrids, developed from Rosa Gallica, Rosa Moschata, Rosa Canina, and Rosa Damascena, earned their name from their numerous overlapping petals - literally "hundred leaves".

The centifolia roses became synonymous with the perfume industry, particularly in Grasse, France. Their intensely fragrant, globular blooms provided the foundation for luxury perfumery, with their clear, sweet fragrance featuring notes of honey and earth. Despite their once-blooming nature, these roses achieved immortality through their portrayal in classical European paintings and their continued use in high-end perfume production.

-min.jpeg)

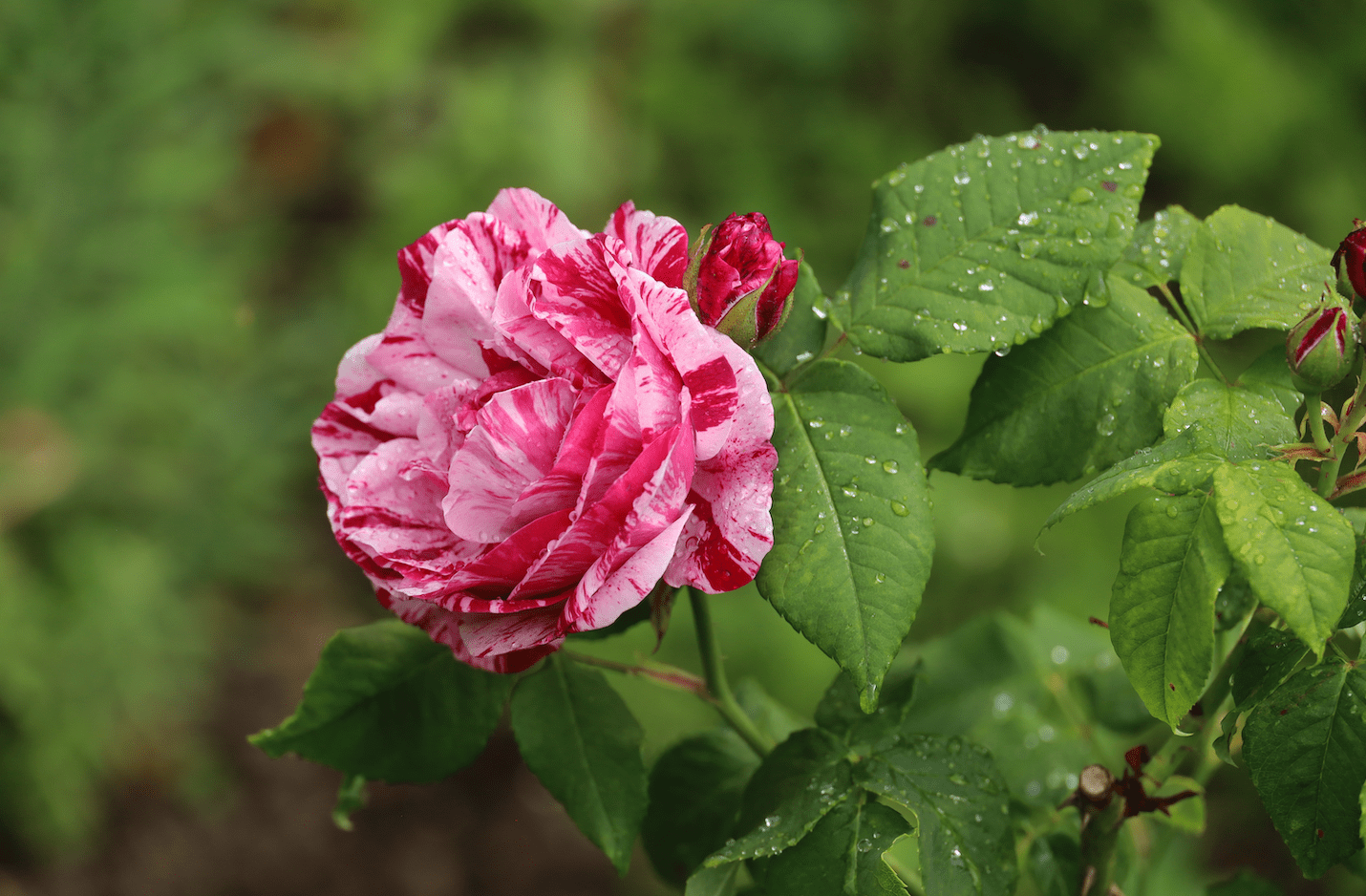

Moss Roses: The Aromatic Sports

In the late 17th century, a remarkable mutation occurred in a centifolia rose garden. A sport appeared with curious "mossy" characteristics covering the flower buds and stems - small, sticky glandular structures that resembled moss but emitted a pine-like fragrance when touched.

This original moss rose, Rosa Centifolia 'Muscosa', became the ancestor of an entire class of roses prized by Victorian gardeners. The moss roses peaked in popularity during the 1840s-1880s, with hundreds of varieties developed in colours ranging from white through pink to deep maroon.

The Revolutionary 19th Century: Creating Modern Classes

Noisette Roses: An American Innovation

The early 19th century witnessed one of rose breeding's most serendipitous successes in Charleston, South Carolina. Around 1802, rice farmer John Champneys received an 'Old Blush' China rose from his neighbour, French nurseryman Philippe Noisette. When Champneys crossed this Chinese rose with a nearby Rosa Moschata, the result was 'Champneys' Pink Cluster'—the first repeat-flowering climbing rose in the Western world.

Philippe Noisette sent seeds of this hybrid to his brother Louis in France, who raised the famous 'Blush Noisette' (or 'Noisette Carnée'). This rose created an immediate sensation in European gardens, with its unusual habit of producing clusters of small, fragrant flowers throughout the season. The famous botanical artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté immortalised 'Blush Noisette' in his paintings, further cementing its popularity.

The noisette roses represented the first successful marriage of Eastern repeat-flowering with Western climbing habits, paving the way for countless climbing roses that followed.

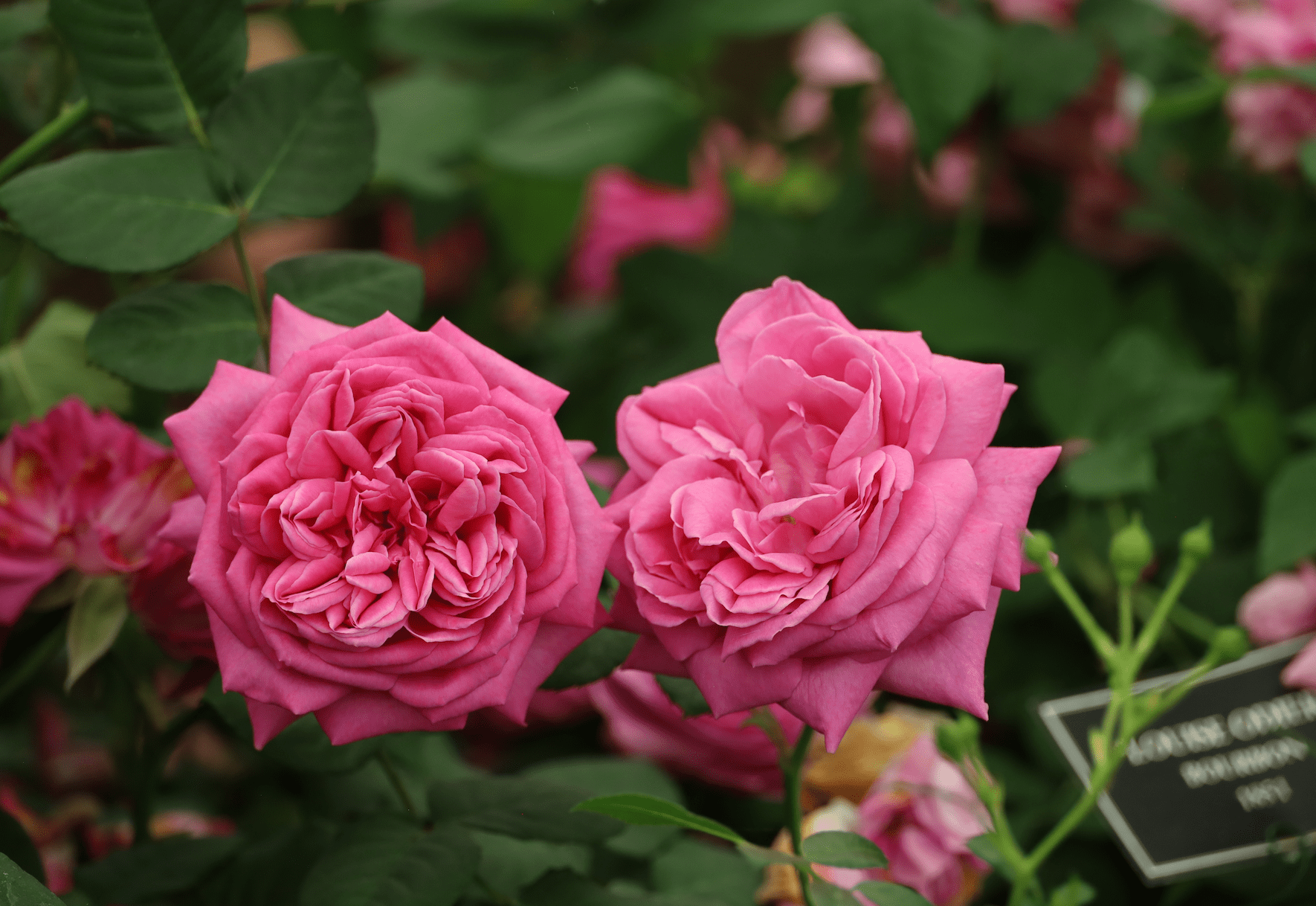

Bourbon Roses: The Island Mystery

Around 1817, a mysterious rose appeared on the Île de Bourbon (now Réunion) in the Indian Ocean. Local inhabitants had been using 'Old Blush' China roses and 'Autumn Damask' roses as hedging plants, and natural hybridisation between these two produced what locals called 'Rose Edouard'.

French nurserymen recognised the potential of this accidental hybrid and brought it to Europe, where it became the foundation of the Bourbon rose class. These roses combined the repeat flowering of their Chinese parent with the fragrance and vigour of their European damask heritage. The Bourbon roses quickly became favourites in 19th-century gardens for their large, fragrant flowers and reliable repeat blooming.

Portland Roses: The Duchess's Discovery

Around 1800, the Duchess of Portland obtained from Italy a rose known as 'Scarlet Four Seasons Rose' or Rosa Paestana. This rose, possibly derived from crosses between 'Autumn Damask' and China roses, became the progenitor of the Portland rose class.

Portland roses, also called Damask Perpetuals, were among the first roses to successfully combine the repeat-flowering ability of Chinese roses with European hardiness and fragrance.

These compact roses, typically reaching only 4 feet in height, produced flowers with very short stems, creating the distinctive appearance of blooms nestled closely among the foliage.

The Portland roses served as crucial stepping stones in rose evolution, bridging the gap between old European varieties and the more complex hybrids that would follow.

Hybrid Perpetual Roses: The Victorian Favourites

By the 1840s, rose breeders had accumulated sufficient genetic diversity to create increasingly complex hybrids. The Hybrid Perpetual roses emerged from crosses between Portland, Bourbon, and Gallica roses, representing the culmination of 19th-century rose breeding.

These roses became the darlings of Victorian society, with nearly 4,000 varieties introduced by 1900. Hybrid Perpetuals typically produced enormous, cabbage-like flowers perched atop long stems, making them ideal for the increasingly popular rose exhibitions that characterised the era.

The development of Hybrid Perpetuals coincided with the rise of competitive rose showing, leading breeders to focus intensively on flower size, form, and cutting quality rather than garden performance. This emphasis on exhibition qualities would significantly influence rose breeding priorities for generations to come.

The Modern Revolution: 1867 and Beyond

Rose 'La France': The Watershed Moment

In 1867, French nurseryman Jean-Baptiste Guillot discovered a remarkable seedling in his Lyon garden that would forever change rose history. This rose, which he named 'La France', combined the hardiness of Hybrid Perpetual roses with the elegance and repeat-flowering ability of Tea roses.

'La France' displayed characteristics that were revolutionary for its time: long, pointed buds that opened slowly into high-centred flowers, carried on long, straight stems. Its silvery-white petals with lilac-pink edges and distinctive fragrance represented a new aesthetic in roses.

The introduction of 'La France' marked the arbitrary but historically significant division between Old Garden Roses (those existing before 1867) and Modern Roses. This single rose became the prototype for Hybrid Tea roses, the class that would dominate rose breeding and gardening for the next century.

The Hybrid Tea Revolution

The success of 'La France' inspired breeders to deliberately cross Hybrid Perpetual and Tea roses, creating the Hybrid Tea class. These roses combined the best qualities of both parents: the hardiness and vigour of Hybrid Perpetuals with the elegant form, repeat flowering, and refined fragrance of Tea roses.

Hybrid Tea roses quickly became the standard by which all other roses were judged. Their characteristic high-centred form, long stems, and single flowers per stem made them ideal for cut flower production, establishing them as the "florist roses" of the modern era.

The breeding focus shifted dramatically with Hybrid Teas, emphasising individual flower perfection over overall plant performance. This change would influence rose breeding philosophy for decades, sometimes at the expense of disease resistance and garden adaptability.

The Genetic Legacy: Understanding Modern Rose Evolution

Recent advances in genetic analysis have revolutionised our understanding of rose evolution. Research has revealed that modern roses represent complex genetic mosaics, with contributions from multiple wild species across continents.

The traditional narrative crediting 'Old Blush' China rose as the primary Eastern contributor has been supplemented by recognition of Rosa odorata's significant role. These tea roses, with their refined fragrance and elegant form, provided crucial genetic material that enabled the development of modern Hybrid Tea and other contemporary rose classes.

Modern genetic mapping has created a "genome variation map" that traces how wild species from Asia, Europe, and other regions contributed to today's garden roses. This research not only illuminates rose history but also provides tools for developing more resilient, climate-adapted varieties for the future.

The Continuing Evolution

The story of garden rose evolution demonstrates humanity's remarkable ability to collaborate with nature in creating beauty. From the simple yellow flowers of 30-million-year-old ancestors to the complex, multi-petalled varieties gracing modern gardens, roses have evolved through a combination of natural selection, geographic separation, and human intervention.

Each rose class - from the ancient Gallicas to the revolutionary Hybrid Teas - represents a chapter in this ongoing story. The genetic contributions of species like the humble Rosa Fedtschenkoana continue to influence roses bred today, while modern techniques promise even more sophisticated varieties adapted to changing climatic conditions.

The evolution of garden roses reflects broader themes in human civilisation: trade routes that connected East and West, the rise of scientific breeding methods, changing aesthetic preferences, and the enduring human desire to cultivate beauty. As we face future challenges of climate change and environmental sustainability, the genetic diversity preserved in wild rose species and heritage varieties provides an invaluable resource for continued innovation.

From monastery gardens to modern laboratories, from chance seedlings to deliberate crosses, the rose continues to evolve - a living testament to the creative partnership between human ambition and natural wonder that has defined our relationship with these remarkable flowers for millennia.